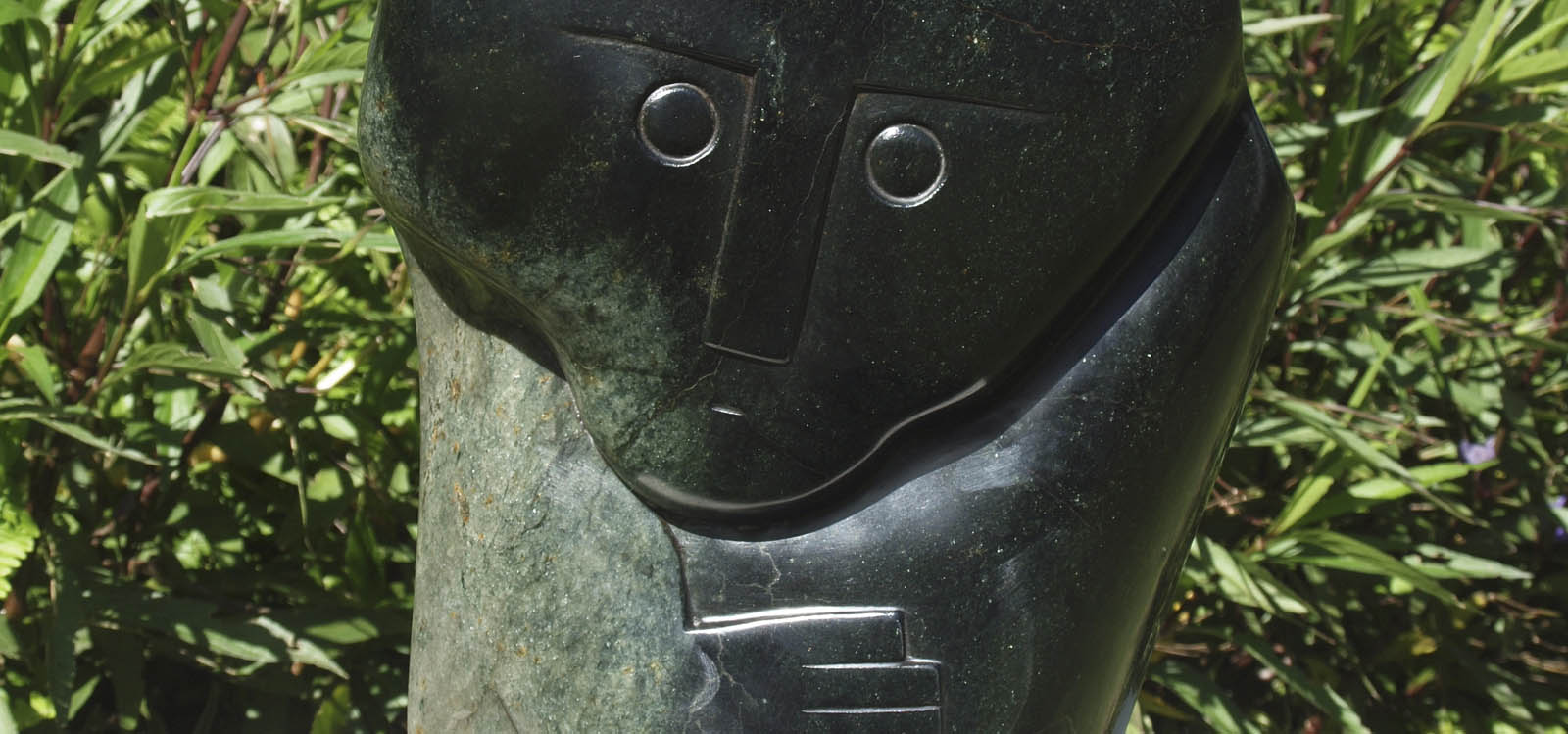

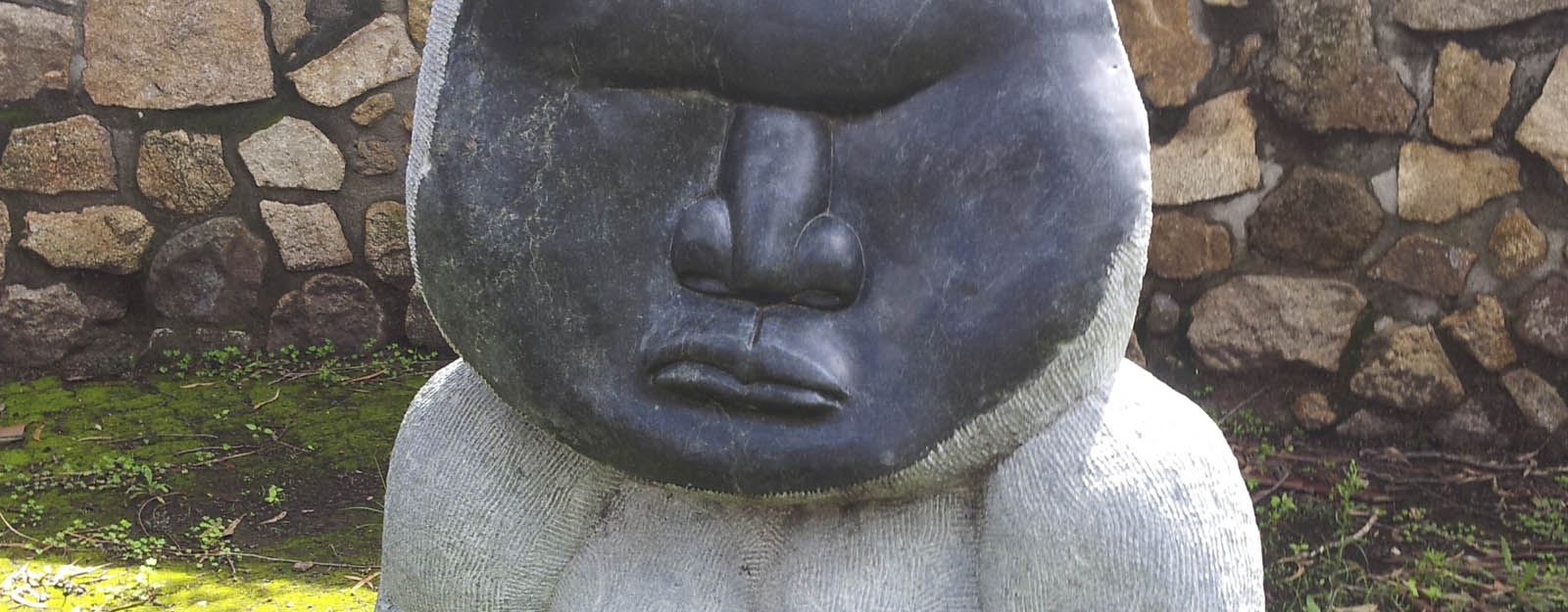

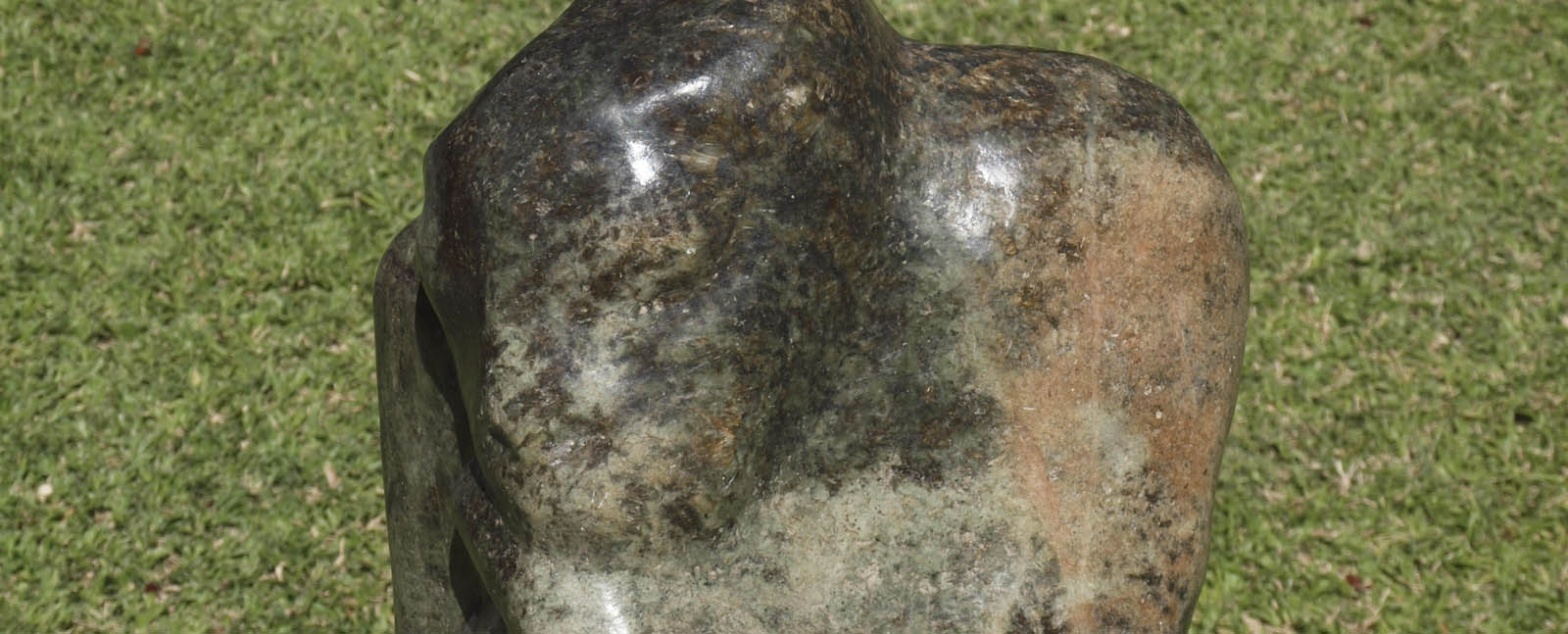

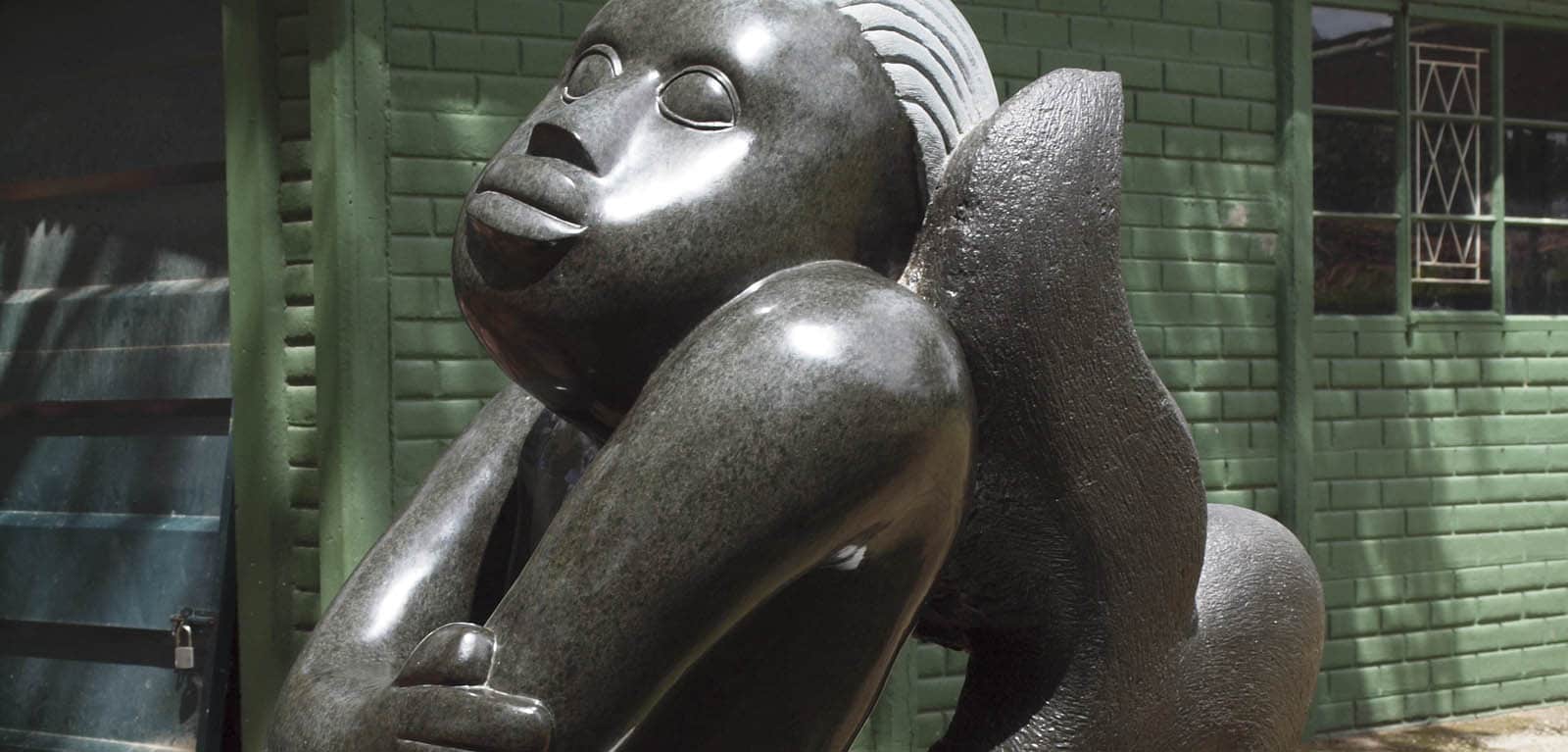

The Shona Sculpture Gallery specialises in stone sculpture from Zimbabwe, often known as the ‘Shona sculpture’ art movement. Although the younger artists may choose modern themes, the striking simplicity of their pieces reveals they too belong to an art movement that first gained international exposure in the 1950s…

Shona sculpture – birth of an international art movement

In 1957, Frank McEwen became the first curator of the new National Gallery in Salisbury, Rhodesia (now Harare, Zimbabwe). McEwen’s previous post had been as curator at the Musée Rodin in Paris. He knew many of the most famous artists of the time, including Picasso (who was himself heavily influenced by African art) and Matisse.

The talent and creativity of some of the budding artists he met in Rhodesia deeply impressed McEwen. He encouraged them to paint (and later to sculpt), emphasising their ‘tribal consciousness’. Because of his contacts in the international art world, he was able to give the movement that later became known as ‘Shona sculpture’ (after Zimbabwe’s most numerous tribe) its first international exposure. However, it is not fair to say that he created the movement.

McEwen encouraged the artists to look inward, to find their so-called ‘tribal subconsciousness’ and express it through their art. Much of the early work was inspired by Shona mythology.

Other sculpture locations of interest

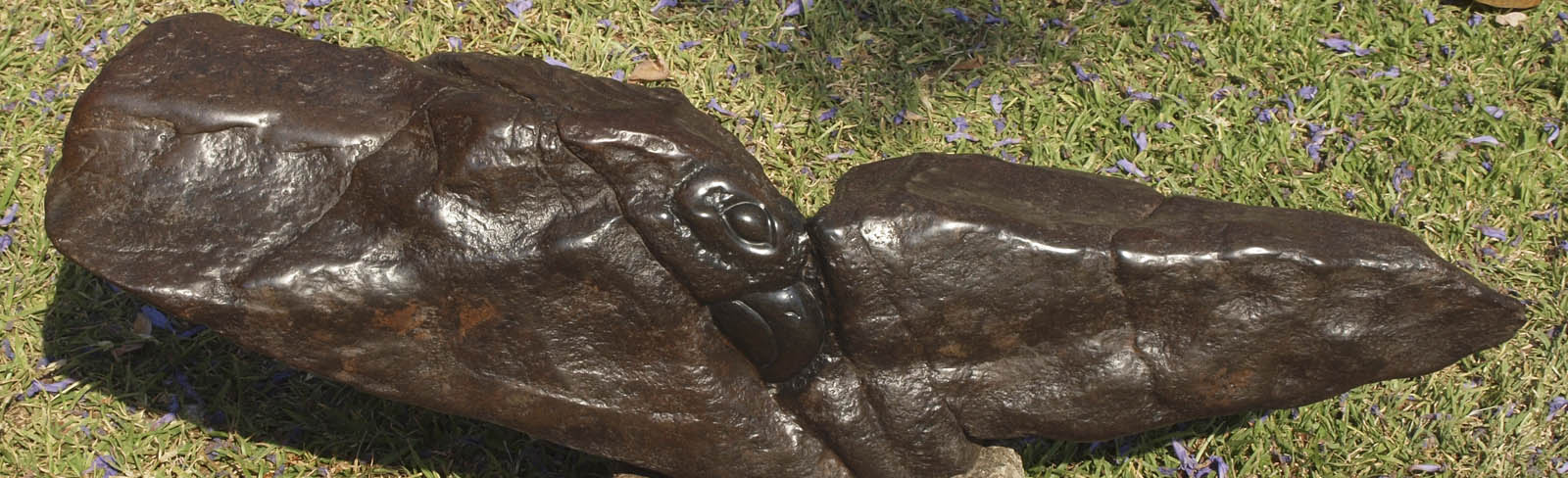

During the 1960s, Tom Blomefield, a white farmer from Tengenenge in northern Zimbabwe, was looking to diversify land use on his farm. Tengenenge is located on the Great Dyke, source of good quality serpentine stone. He set up one the first, and now the largest and best-known, sculpture communities – many famous artists have worked there. Other sculpture communities were located at Cyrene Mission near Great Zimbabwe and later at Chapungu in the suburbs east of Harare.

Another hub formed around influential artist Joram Mariga, who lived and worked in the Nyanga area of the eastern Highlands. He is revered as ‘the father of Shona sculpture’. When McEwen saw Mariga’s work he was greatly impressed. Joram’s creativity had already found means of expression, without Western influence via McEwen’s Workshop School. This neatly disproves the theory that has been propounded by some that the entire art movement was a colonial construct.

World-renowned names emerge

Over the following sixty years, many first- and second-generation artists have become famous worldwide. They are classed among the world’s most talented sculptors.

For more works by the most famous names in the Shona sculpture movement, visit our UK-based web gallery www.guruve.com

Names to look out for include:

Henry Munyaradzi

Nicholas Mukomberanwa

Joseph Ndandarika

Bernard Matemera

John Takawira

Bernard Takawira

Boira Mteki

Sylvester Mubayi

Colleen Madamombe

Brighton Sango

Brighton was a leading light of the second generation until his untimely suicide in 1995.

Overseas exposure for Shona sculpture

Shona sculpture is Africa’s best known contemporary art movement.

Seminal group exhibitions organised by McEwen during the 1960s-1970s period include Musée Rodin, Paris, France and at the Institute for Contemporary Arts (ICA), London, UK.

Collectors include Prince Charles, who opened a major exhibition at the Barbican centre in London in 1980.

Subsequent to that, various Harare galleries organised important exhibitions, particularly Chapungu and Matombo Gallery. These include at Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Ohio, USA (1991); pieces on permanent display at Atlanta International Airport; touring exhibitions in Kew Gardens, UK (2000) and various botanic gardens in USA.

However, Zimbabwe’s departure into the economic and political ‘long grass’ began with the farm invasions of 2000. As a result, there was a collapse in tourist numbers meaning that fewer international visitors see the sculpture in Zimbabwe, and even fewer are tempted to take works home. Overall, general international awareness of Shona sculpture as an art form has decreased substantially in the following two decades.

Since 2000, all of the major galleries in Harare have closed. Clearly, this has had the knock-on effect of making life for the sculptors increasingly difficult. It was in the context of the impending collapse of the entire promotional infrastructure for Shona sculpture in its home city, that we opened the Shona Sculpture Gallery in 2016.

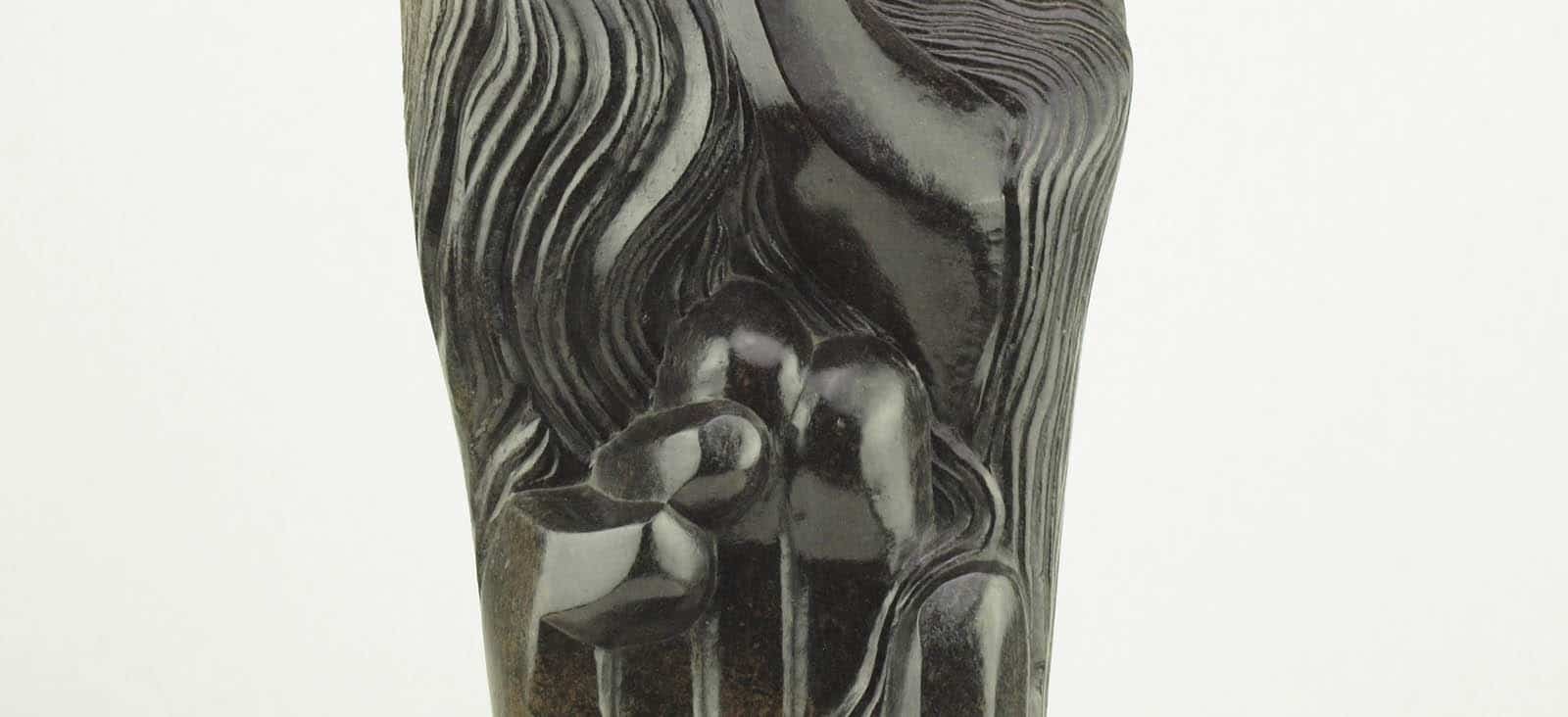

The future of Shona sculpture

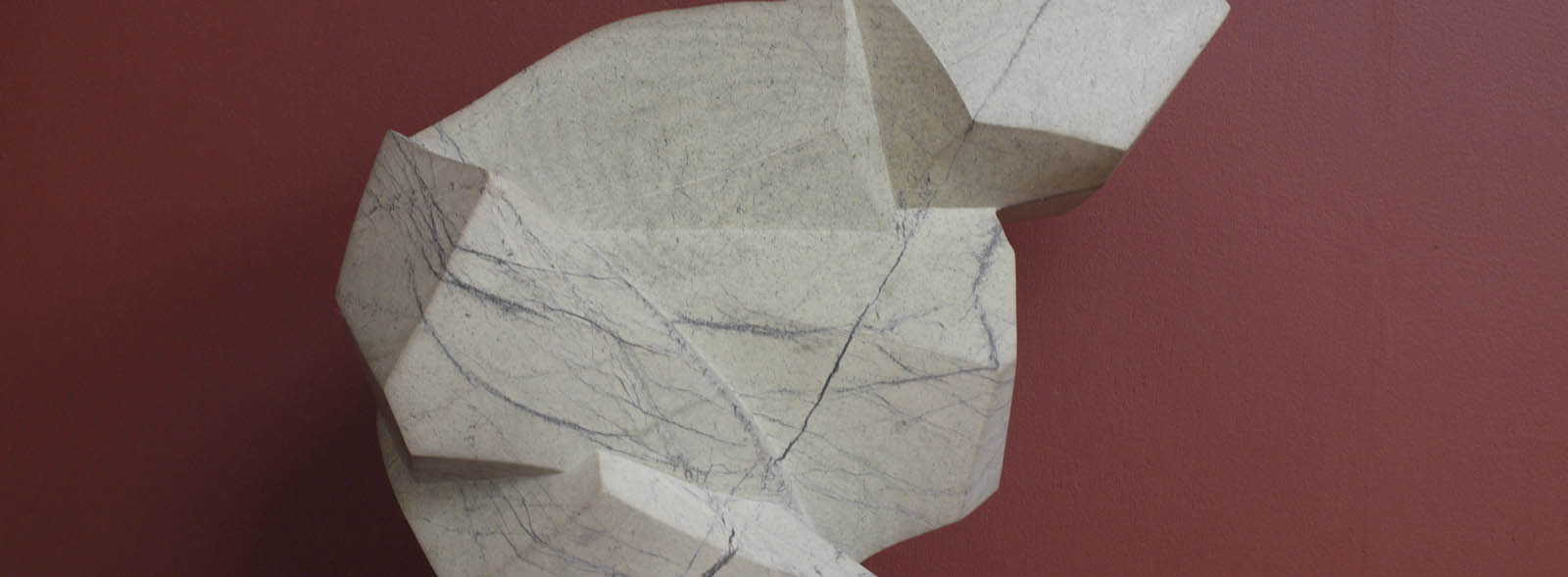

There is a new generation of amazingly talented artists working in Zimbabwe today, mainly in urban environments. They are exposed to modernity – technology, education and social change. However, most retain rural family ties that ground them in Shona cultural tradition and beliefs. As a result, these young artists combine the two, building on the old school of ‘Shona sculpture‘ and creating a new modern style.

A gallery for the future

For 20 years, we have immersed ourselves in this niche art movement via our UK company www.guruve.com. We have become world experts in Zimbabwean Shona stone sculpture. The natural progression was to open a gallery on the ground in Zimbabwe.

We invested all our energy and enthusiasm into this new Harare-based project, the Shona Sculpture Gallery. With our passion, knowledge and experience, we are the natural successors to those first distinguished galleries and promoters. We support and promote talented young Zimbabwean sculptors, and work to raise the profile of the sculpture movement as a whole.

This text is copyright and is the intellectual property of the Shona Sculpture Gallery (please see statement on our homepage).

Related links:

Sculpture process – stages in the process from raw stone to sculpture

Types of stone commonly used by the best Zimbabwean artists

Common themes in Zimbabwean sculpture

Shona spirit beliefs and how they inspire Zimbabwean sculpture

Life as a sculptor – comments and insight from Zimbabwean artists

Care and repair – helpful guidance on looking after your sculpture