Certain themes recur in Zimbabwean sculpture, with each individual artist having their own take on common subject matter. Here’s some background on a few of the most frequently seen titles…

Njuzu (Water Spirit)

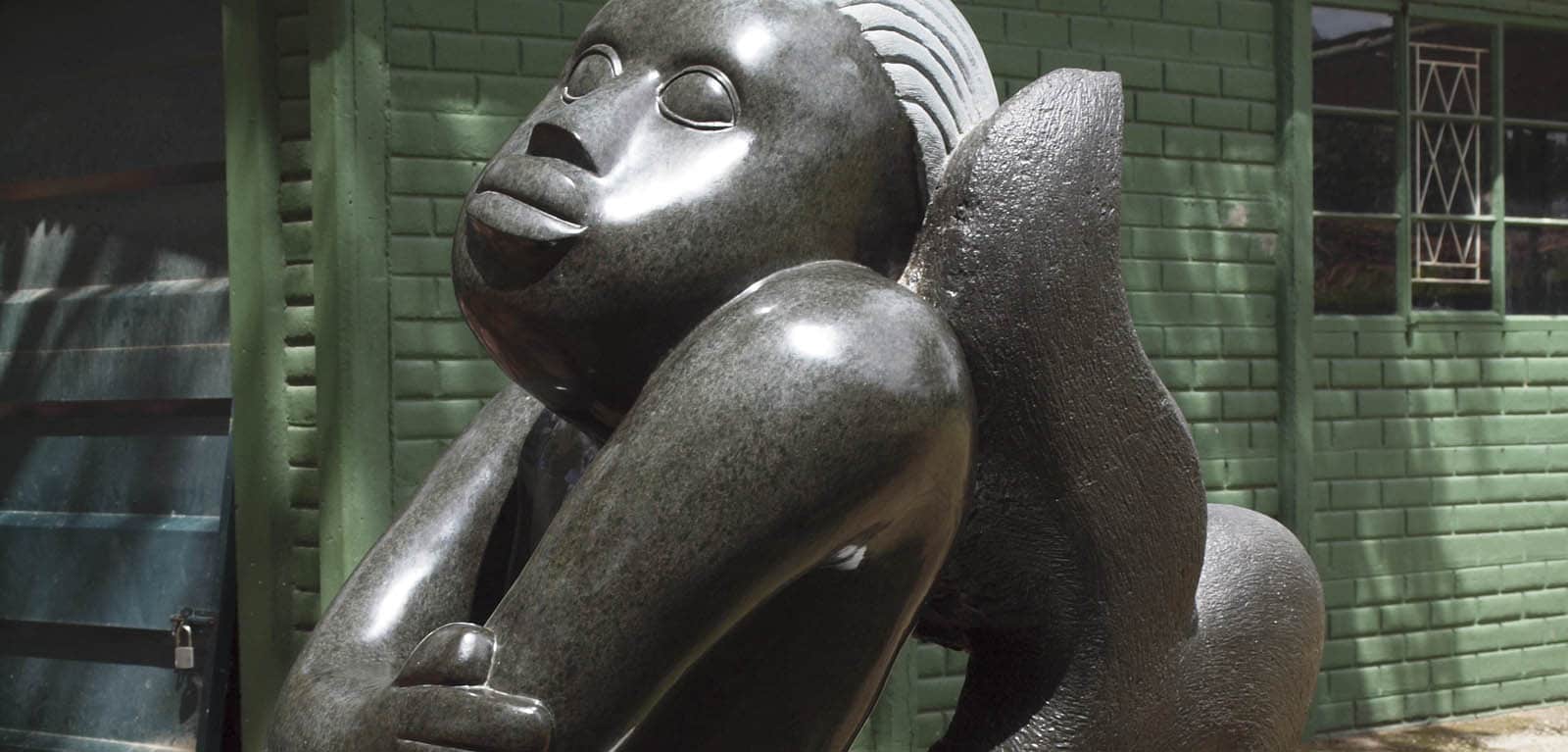

Shona beliefs ascribe a spiritual presence to inanimate objects. The spirits that inhabit rivers, lakes and streams are called ‘njuzu‘. The njuzu is half human, half fish and is always female, so it is no surprise that it is often represented visually in Shona sculpture as something akin to a mermaid.

As you can see from the story below, the njuzu story is so important to Shona beliefs as it explains how certain humans come to have spiritual capabilities.

The Njuzu story

The njuzu lives deep in the lake, where there might be a cave and that is where the njuzu would live.

Near one of these special lakes, which humans can’t perceive, you can find white clothes (belonging to the njuzu) drying on the trees early in the morning, but as it warms up they disappear.

The njuzu‘s purpose is to groom or train the spirit medium or n’anga.

A person who has the potential (even if they don’t realise it) to become a n’anga might disappear into the water. They might be away a long time, perhaps even up to a year. Their family must not cry or mourn for them, because they have just gone to another place (the spirit world) – they’re not dead, but, if the family does mourn, they will die and their body will be washed up on the shore.

The relatives have to perform a ritual libation (pouring an offering on the ground) to tell the spirits that the person has gone to the spirit world and to ask the spirits to look after them.

While they are away, that person is trained in the spirit world by the njuzu and when they return to the physical world they are very likely to become a n’anga or traditional healer – because they have already been to the spirit world and they know how to travel between the two dimensions.

Totems

The totems come from way back in history and are based on the characters of particular human beings, reflecting assuming nature of various other species, so a brave person might have been assigned the totem of the lion. All their descendants would have the lion totem too.

In history, after a big battle, the victor would be given a new name to commemorate the victory. The land of that group is known by the totem name too, so it links families with their homeland. To communicate with the ancestors, you call on spirits of the same totem.

Women take on the totem of their husbands, and people of the same totem are not allowed to inter-marry, so this system also works to prevent interfamilial or incestuous marriages. In the old days, same-totem marriages were taboo, but in these new days of urbanisation the younger generation do sometimes marry within totems. The groom has to pay an extra cow in lobola (bride-wealth) as a fine, as they have broken a rule.

Strangers of the same totem greet each other as relatives, because they know that way back in time they are related.

People are proud of their totem and they want to be part of a strong and numerous totem. This is one of the contributing factors towards men wanting large families in general and sons in particular.

Family

Family is at the heart of all society. In Zimbabwe, as in much of Africa, this is particularly true because there is no social security system. The extended family network ensures that the more vulnerable members of society are cared for.

The complicated network of social ties between different family members, their responsibilities and the expectations of their peers, are frequently expressed in the work of many of the sculptors.

Through the sculptures, and the attitudes and beliefs they express, outsiders can gain valuable insight into the functioning and structure of Shona society. We can also see how it is changing over time, particularly the influences of modern living and urbanisation, as reflected in works by the different generations of Shona artists.

The commonest theme must be ‘mother and child’, replicated ad infinitum in generic roadside works in soapstone, but a mother’s love for her child and the family’s value placed on her fertility can be the inspiration for some fantastically moving and original works of art. However, some other themes may need a little more explanation…

Muroora (Daughter-in-law)

This is a very common theme in Shona sculpture, and represents a young woman at the time of marriage. Therefore, in many ways it is a celebration of the ideal of female beauty – of women when at their most beautiful and fertile – but there are other aspects to the idea as well.

The muroora story

The muroora joins her new husband’s household at the bottom of the pecking order. The family expect her to wait upon them like a servant, kneeling to serve them food, and show all the family the proper respect. So she also embodies humility and servility, and also downright hard work!

She also has a strong caring role, as she must take care of not only her husband but also his parents (a role that continues until their deaths). Unsurprisingly, friction between a woman and her in-laws is not a cliché only in Western society!

The muroora also cares for any children within the household – it could be her husband’s younger siblings or the children of any of his brothers, who also live in the same household.

Muroora as an ideal is also strongly tied up with fertility. Shona society expects a new bride to become pregnant within a few months of marriage. If this doesn’t happen, there is a lot of pressure put on the new wife – as it is presumed to be her fault, not her husband’s.

So Muroora is the perfect idealised African woman – beautiful, fertile, respectful, caring, hardworking and uncomplaining. Don’t forget that the vast majority of sculptors are men, and their idea of the perfect woman may not be what modern Zimbabwean women aspire to!

Ambuya (Grandmother)

Ambuya is the other end of the spectrum to the muroora – she is the grandmother who is head of the household, and her word is law. All the younger women defer to her and look after her needs.

The ambuya story

As time passes, the young wife has children, which increases her status within the household. When she first becomes a mother, a young woman is no longer called by her given name and instead is addressed as Mai Baby-name, so ‘Mother of so-and-so’. Her identity is lost into that of the child she has produced. She continues to be addressed as Mai First-child until she becomes a grandmother.

Interestingly, it is only when one of her daughters has their first child, that a woman gains her highest level of respect within society. Her friends and relatives will be delighted that they can finally call her ‘Ambuya’ and thereby show the proper respect due in accordance with her age and life experience.

It shows that Shona culture is recognising her progression into the third generation tier of society. When your daughter has had a baby, and you have assisted her at the birth, you have become an elder.

Ambuya is also a term of respect used by the younger generation to older women (as it is presumed they are grandparents).

Sekuru (Grandfather)

Although sekuru literally means grandfather, it is also a widely used term of respect applied by younger people to an older man.

In particular, in Shona society you must call all your male relatives from your mother’s family ‘sekuru’, as it is a term of respect and you must humble yourself towards them.

A sekuru is an elder man of society; someone who has lived a whole full life and is now ‘winding down’ physically (the term mundara is used for an older man who is still running around organising things!) However, a sekuru still plays an active role in the social fabric, as he is called upon to settle disputes and younger individuals within the community may come to him for advice. He may well also be part of the council of elders within a village or rural area, who are collectively responsible for local decision-making at a level below the local chief (mambo).

This text is copyright and is the intellectual property of the Shona Sculpture Gallery (please see statement on our homepage).

Related links:

Shona sculpture movement – Zimbabwe’s art history

Sculpture process – stages in the process from raw stone to sculpture

Types of stone commonly used by the best Zimbabwean artists

Shona spirit beliefs and how they inspire Zimbabwean sculpture

Life as a sculptor – comments and insight from Zimbabwean artists

Care and repair – helpful guidance on looking after your sculpture